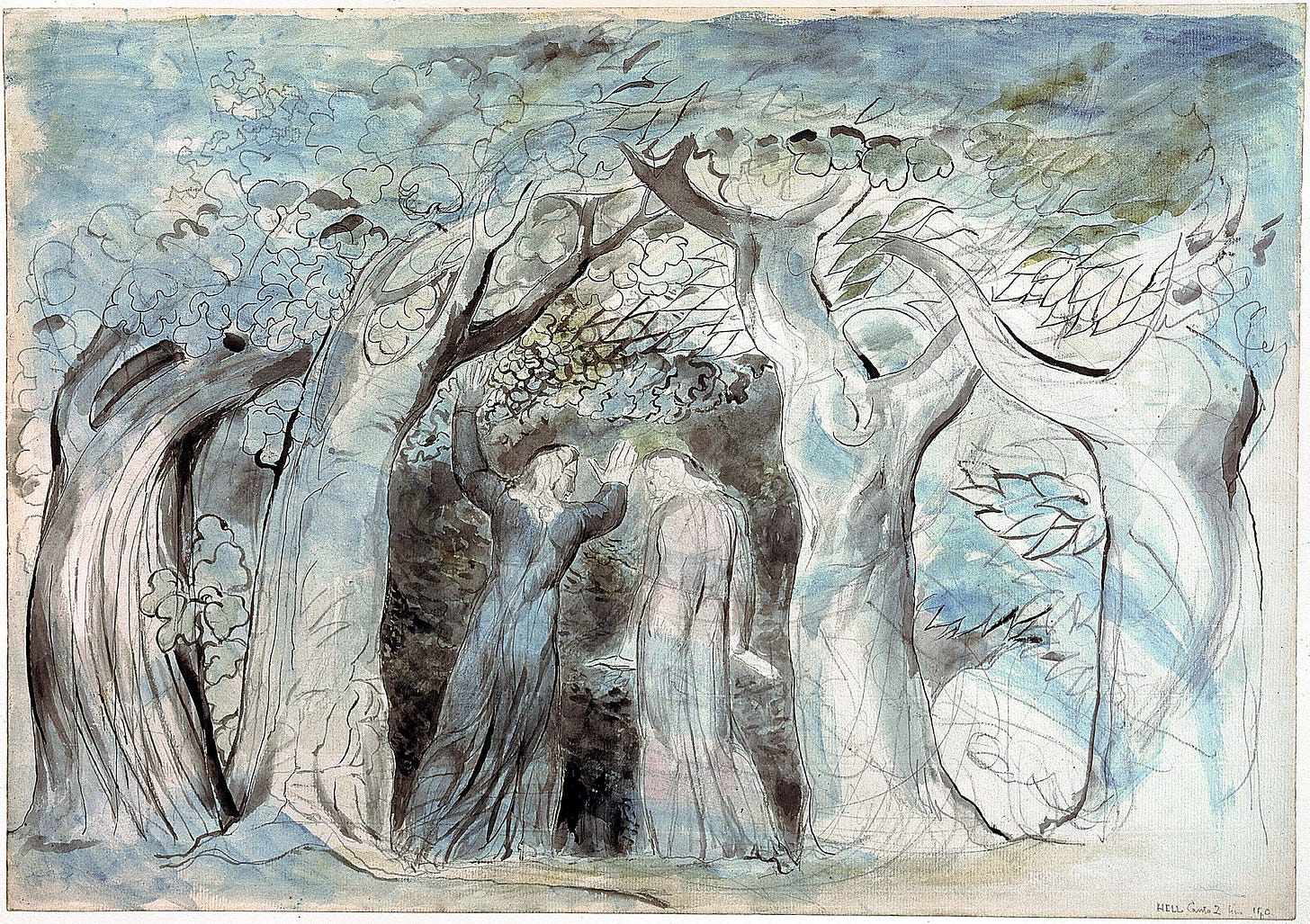

In the dark wood of mid-life crisis, Dante finds himself lost, a predicament that resonates with the modern condition despite being written in the 14th century.

Unlike his classical predecessors, Dante’s journey through Hell isn’t motivated by curiosity but by an existential despair that anticipates our modern malaise.

Dante has desires but they are disordered and as such he is lost, requiring him to descend to Hell and experience his true self before finding himself again.

The literary tradition of underworld journeys stretches back to antiquity.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus travels to the underworld to consult the prophet Tiresias, performing elaborate rituals involving sacrificial blood to facilitate his entry. Similarly, in Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas descends to meet his father Anchises, bearing the golden bough as his ritual passport. Both heroes enter the underworld with specific purposes and prepared through sacred rites.

Dante’s only rite is his commitment to self-transcendence. With the Divina Commedia, we may think we’re in the 14th century, in fact we are already here and now.

Dante’s approach differs fundamentally. His passport isn’t a ritual object but his existential crisis—the dark wood representing the despair that has brought Modern Man to his knees.

While Odysseus and Aeneas sought specific individuals, Dante unwittingly seeks himself. His guide Virgil, like Morpheus offering Neo the red pill, presents him with a choice: continue wandering aimlessly in meaningless existence or undertake a transformational journey into reality—not an external reality, but the truth of the human condition.

This transformation echoes the Orphic mysteries that likely influenced Virgil’s underworld narrative. The Orphic tradition of ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, centered on death and rebirth, requiring initiates to symbolically die to their old selves before emerging transformed. Similarly, Dante must metaphorically die to his disordered desires before ascending toward paradise, the space and time of ultimate concern.

While the Inferno vividly depicts sinners and their punishments—from the lustful buffeted back and forth by the terrible winds of a violent storm to counterfeiters suffering loathsome dropsy-like disease—these encounters serve primarily as mirrors for Dante himself, fooling us with their apparent supersalience. Each circle reflects aspects of human nature that Dante must recognize within himself before transcending them. His journey isn’t merely observational but transformational. Immersed in Hell, Dante discovers he is actually immersing himself in himself.

Virgil, representing Natural Reason, can only guide Dante through Hell and Purgatory before being left behind at Paradise, thus representing the limits of the natural intellect. Complete transformation requires moving beyond reason to love, symbolized by Beatrice who leads him into supernatural virtue. Love is not irrational, as the Romantics would later claim, but super-rational. True knowledge is not propositional, but perspectival and participatory. It can’t be explained, it must be experienced.

The brilliance of Dante’s vision lies in its psychological depth. Unlike the ancient heroes who return relatively unchanged from their underworld excursions, Dante emerges fundamentally transformed, serving as a blueprint for what the poem may elicit, at its finest, in the reader, in you and I.