Between originality and derivation

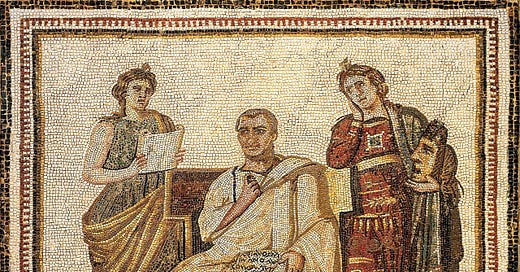

Imagine Virgil - the Roman poet, not your neighbour - leaning over his (wax) tablet and asking ChatGPT to write an epic poem in the style of Homer:

Scribe carmen in hexametris in stilo Homeri poetae Graeci de itinere Aeneae, Troiani superstitis, qui vaticinium sequitur ut novam urbem in Latio condat quae Roma futura erit, sed non antequam indigenas vincit et in familiam regiam matrimonio iungitur.

Write an epic poem in hexameters in the style of the Greek poet Homer about the journey of Aeneas, a Trojan survivor, who follows the prophecy to found a new city in Latium that would turn out to be Rome, but not before he’s conquered the natives and married into the royal family.

Virgil’s masterpiece the Aeneid, one of the founding narratives of European cilization, was both a work of remarkable originality and of curated derivation.

In composing a foundational piece, Virgil built on pre-existing foundations: the Homeric poems the Illiad and the Odyssey (each serving as the bedrock for the first and last six books of the Aeneid, respectively), Greek and Etruscan myths about Aeneas that predated Virgil by centuries (as exemplified by Greek vases from the sixth century BC expressing early mythological accounts of Aeneas founding a new home in Etruria), Rome’s national legend about the war fought under Romulus against the Sabines, which preserves an Indo-European myth about conflict between gods of sovereignty and gods of fecundity, and the rest of the Epic Cycle, a collection of ancient Greek epic poems (containing the Iliad and the Odyssey, but not limited to them) composed between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, and based on oral traditions, focusing on the Trojan War and related mythological events.

So we can see that by the time Virgil sat down to bite the Augustan epic bullet, his intelligence had been trained on a massive corpus of sources. And those sources had in turn been trained on other sources, and so on, through mise-en-abîme, to the depths of human intelligence and distributed cognition.

No work is born in a vaccuum, nor is a work responding to the needs of a community, or emerging from the nebulae of textual communities, simply the result of derivation, or probabilistic or stochastic prediction. The originality of a text like Virgil’s Aeneid lies in the space between purpose, language, sacredness and emotion - all the stuff of human value rather than fact, as we might say.

A story built around the sacred mission of pulling the thread of civilization forward against the backdrop of loss, overwhelming passion, relentless violence, and unwavering commitment is always more than a story, more than an account. As readers have been finding out over the last 2,000 years, it is an encounter, an experience that offers fresh insight each time. Unlike the parasitical output of machines mimicking moral, value-driven centres, a story bubbling up from the depths of collective human experience is more than an artefact.