On the outside looking in

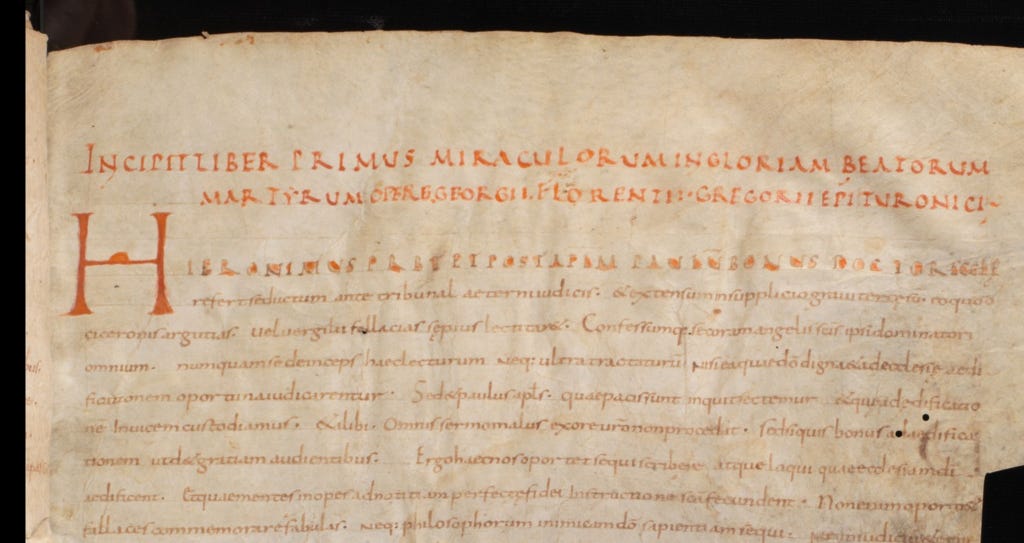

Titles tend to be located as much outside the text as inside.

It took titles centuries to achieve this ambiguity.

In the beginning, there were no titles, and God …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.