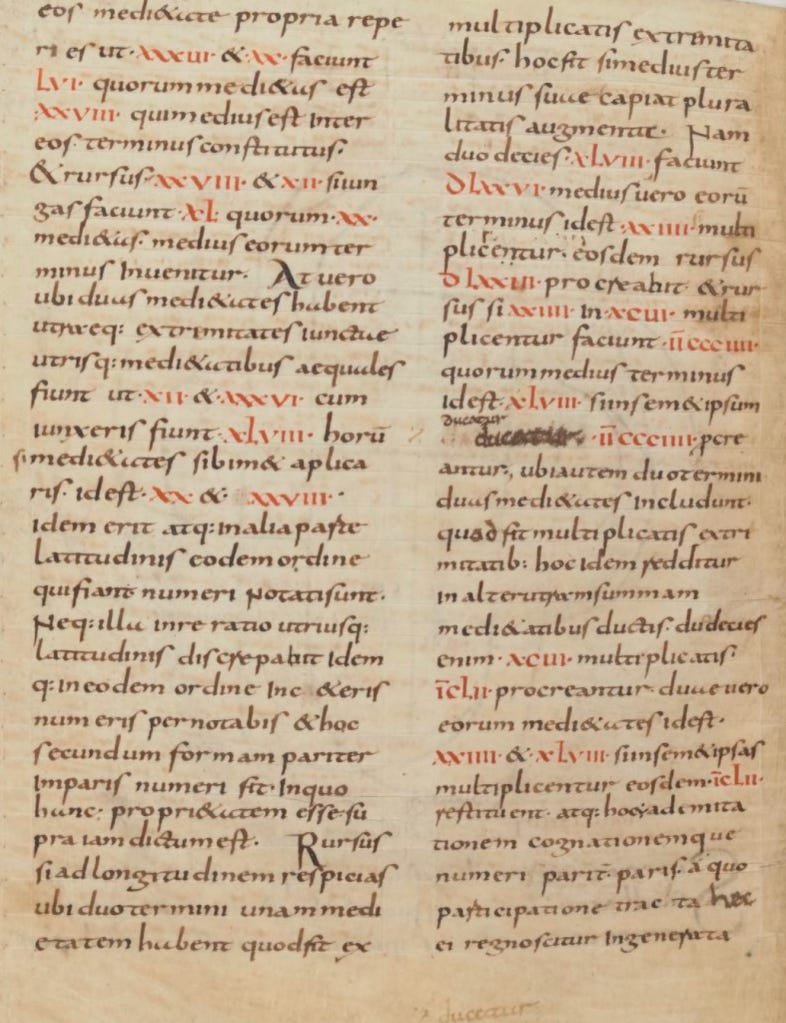

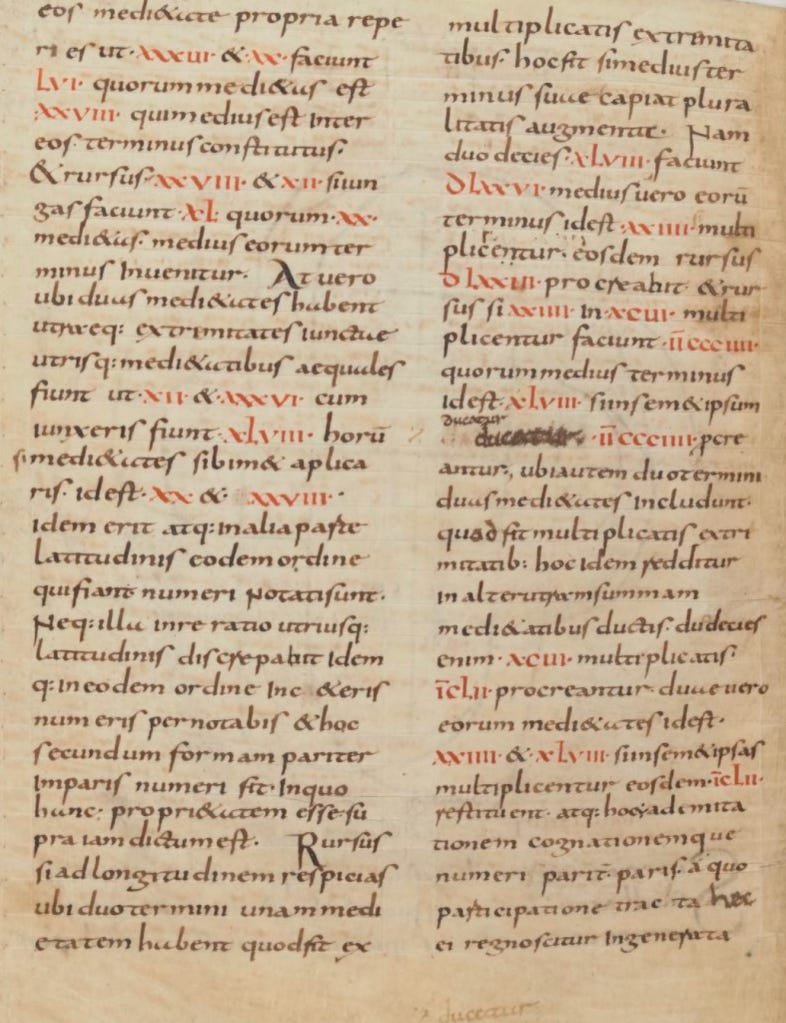

Medieval calculations

There are many sad truths about medieval manuscripts. They took extreme…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

There are many sad truths about medieval manuscripts. They took extreme…

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.