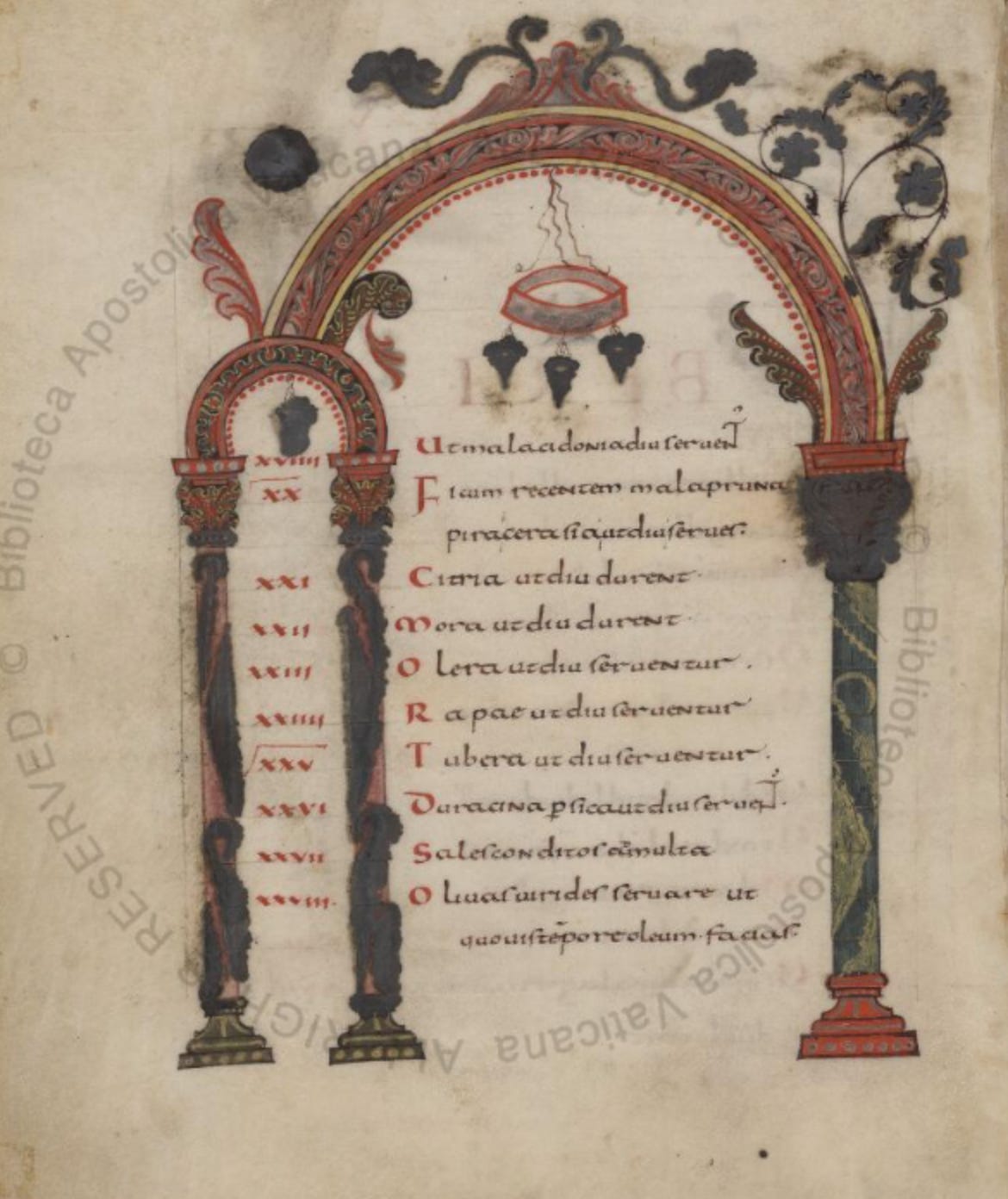

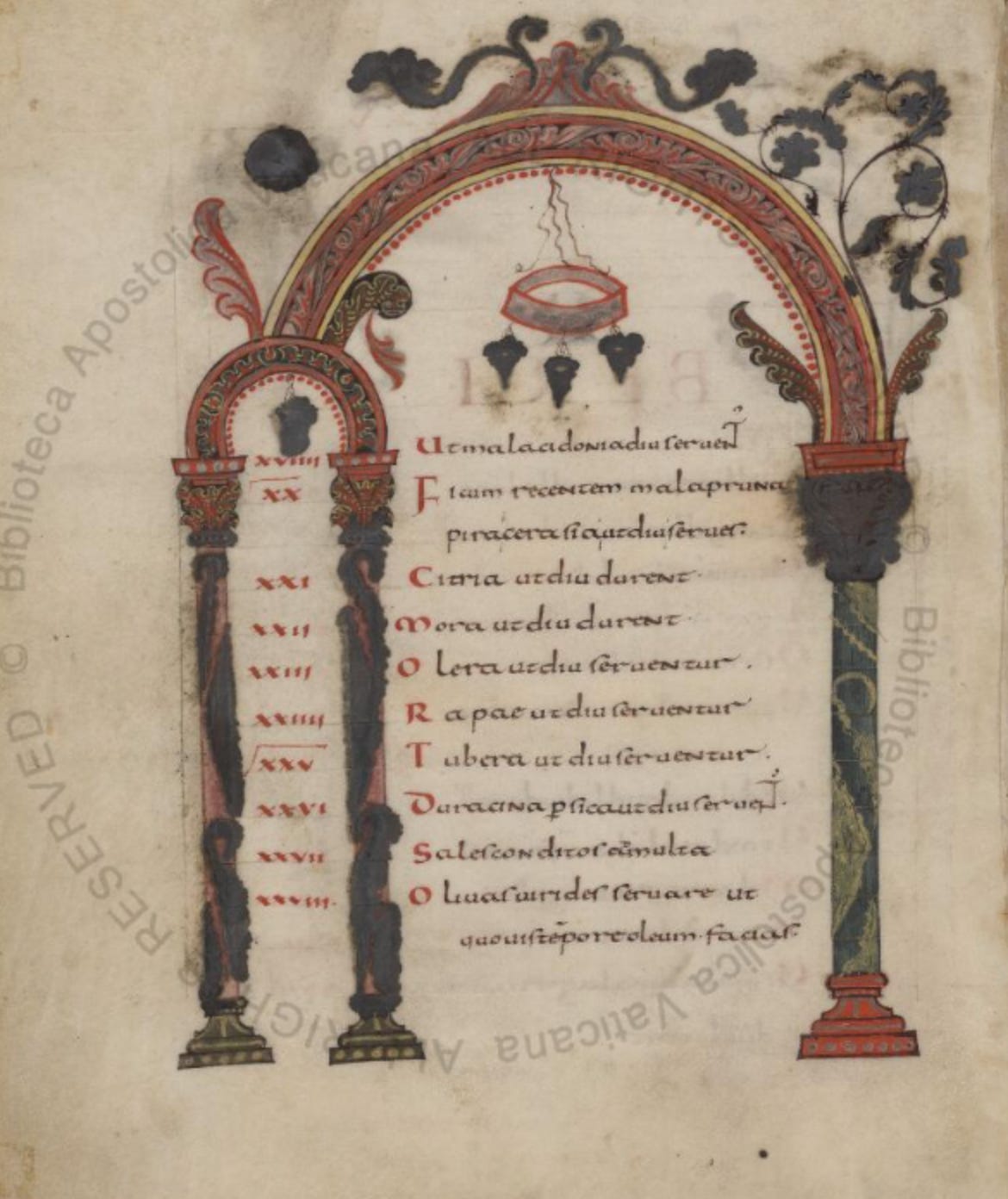

Unattempted recipes

The proof is in the pudding, and ancient cookbooks are …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

The proof is in the pudding, and ancient cookbooks are …

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.