The neo-scroll turn

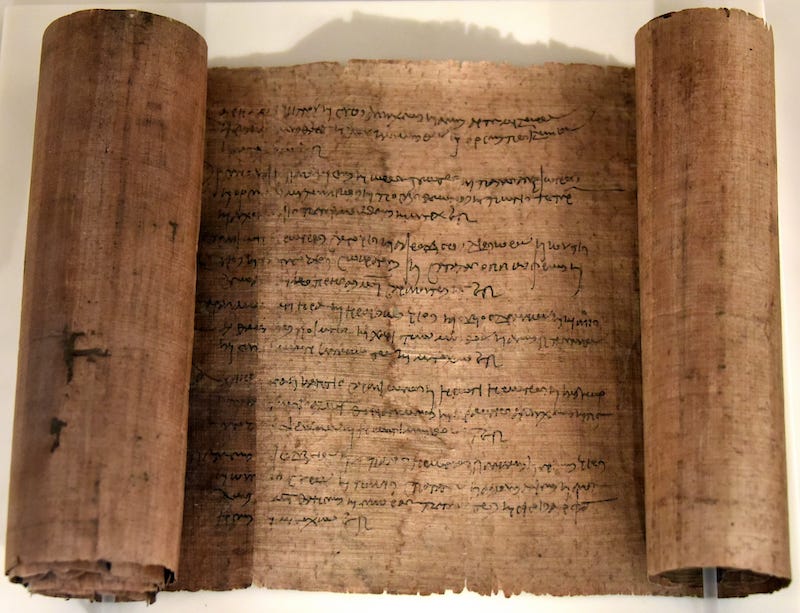

We are so surrounded by books that we forget how revolutionary the emergence of the codex - the bound book made up of stitched sheets stacked together and enclosed between a case - was to the cultures around the Mediterranean and beyond. The book as we know it.

Writing predates the advent of the book by several millennia, but the success of the latter wa…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.