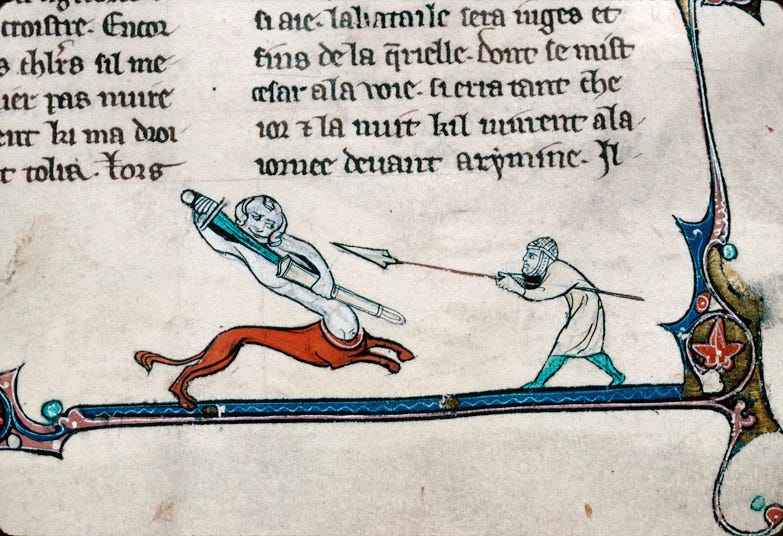

The enduring charm of hybridity

In at least one respect, we're not too far away from the Middle Ages, and that's in our cultural bend towards hybridity.

I'm not taking about hybrid cars, or maybe I am.

One question historians very rarely ask is: what's in a hybrid? Sure, the word is familiar enough, and it conjures up images ranging from the hybrid cars I mentioned to creatures of fanta…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.