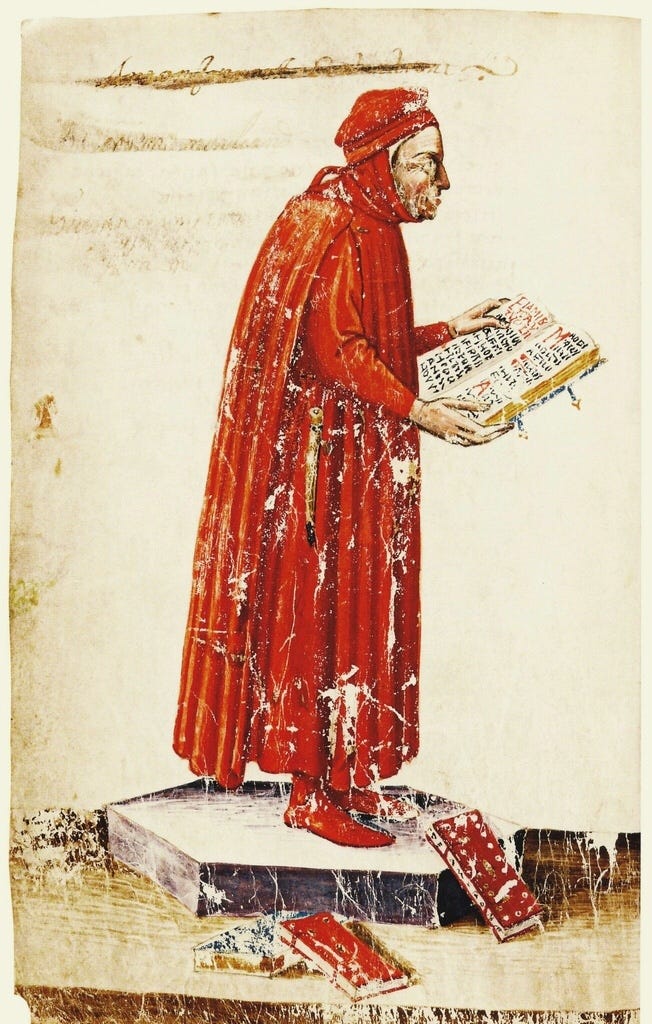

Medieval cultural influencers

No one mentions notaries, secretaries and other such public functionaries and thinks of power and influence. It's true, in countries subject to civil law, a notary is required to authenticate a power of attorney, write up a will or transfer property. But apart from that, notaries are not seen as agents of cultural innovation, but petty secular saints in…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.