Fictions

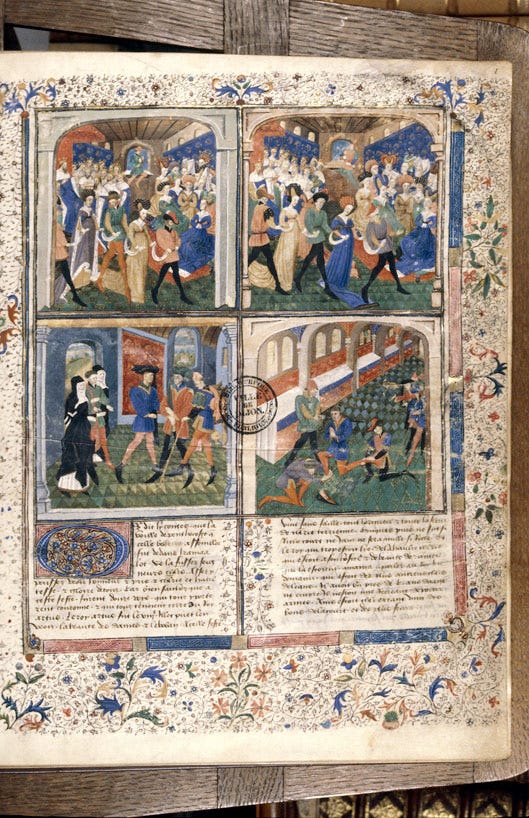

A manuscript of the Tristan and Iseult stories in prose, Dijon, Bibliothèque Municipale, 527

It is generally agreed that the tradition of the European novel begins with the compellingly bizarre Satyricon of Petronius. 1st-century Romans were finally able to consume a literary work which was neither history, philosophy, essay, personal reflection on natu…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.