Genetic indeterminacy

Medieval manuscripts are books. A book is a written artefact. What is written is the opposite of what is spoken, which is oral. Writing is about literacy, speaking is about orality. Therefore, a book is a literate object, anything spoken is an object of orality. That's a neat distinction. And it's wrong.

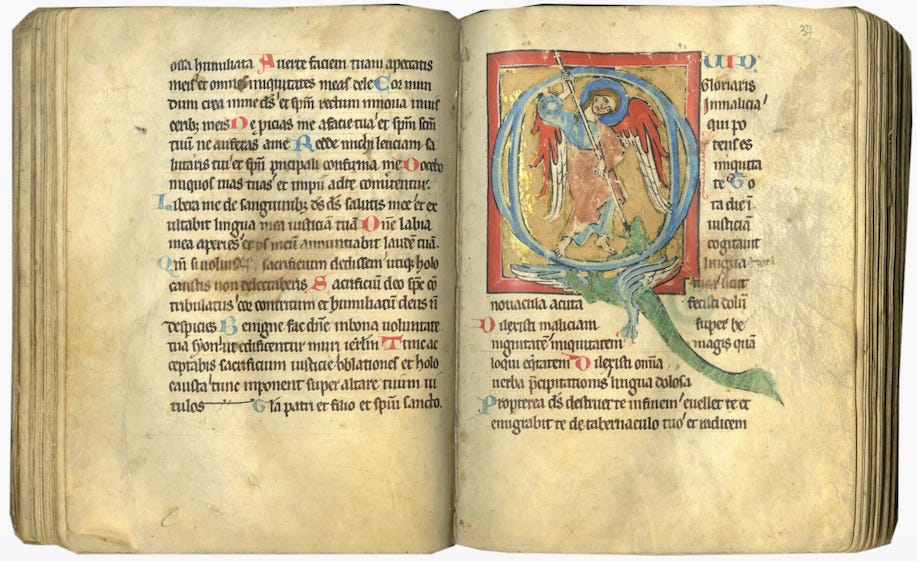

A medieval manuscript is a genetic indeterminacy. …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Biblonia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.